As boomer owners prepare to sell, a push for workers to buy

Your company’s next owner could be sitting in a cubicle down the hall, assembling parts on a factory floor or laboring on a construction site down the street. That, at least, is the hope of a burgeoning movement concerned about what will happen to the thousands of small and mid-sized businesses owned by baby boomers in Central Pennsylvania.

Most, if not all, of those owners will be looking to sell their companies over the next few years.

While many will turn to family members, industry peers or even private equity firms, an effort led by a Lancaster-based nonprofit is hoping owners will at least contemplate handing over the reins to employees.

“Widespread ownership transitions in our community offer us an opportunity to harness the moment to retain local jobs, root wealth locally and maintain a vibrant local economy. Employee ownership structures are a powerful way to do this,” said Craig Dalen, director of impact business strategy at Assets, the nonprofit that is leading the charge to spread awareness about employee ownership.

The nonprofit is describing the wave of anticipated sales as a “silver tsunami.”

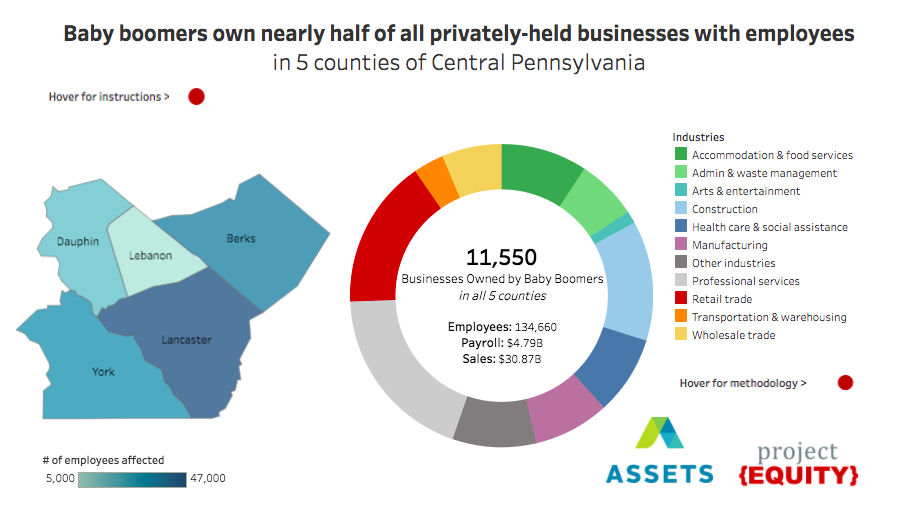

At stake is the fate of roughly 11,550 businesses employing nearly 135,000 people in Berks, Dauphin, Lancaster, Lebanon and York counties, the areas covered by Assets, according to data the nonprofit gathered from the most recent U.S. Census survey of small-business owners, taken in 2012. The region’s boomer-owned companies represent $30.87 billion in sales and $4.79 billion in payroll.

As it looks to put employee ownership on the menu of exit strategies, Assets is collaborating with local lawyers, advisers and business owners, as well as an Oakland-based nonprofit, Project Equity, that is undertaking similar campaigns in other communities around the country.

Employee ownership remains relatively rare. Out of nearly 6 million companies of all sizes nationwide, just under 7,000 are held by employee stock ownership plans, or ESOPs, one of the most common vehicles for selling a business to its workers, according to the National Center for Employee Ownership. Another 1,000 companies operate under other forms of employee ownership, Project Equity estimates.

Employee ownership is not a fit for every business, its advocates acknowledge. And it is not the only way to preserve local control. Passing a business from a parent to a child or children, for example, also keeps wealth and ownership in a community.

But it is better than simply shutting a company down, which is often the path of least resistance, or selling to a third party from outside the community, said the co-founders of Project Equity, Alison Lingane and Hilary Abell

“Typically that means you’re going to lose at least some portion of the jobs in administrative and back-end operations,” said Lingane, noting that a company’s spending and profits also may leave the community after a sale.

Advocates of employee ownership want to ensure departing owners are rewarded fairly for what often represents their life’s work. But they also hope owners will value other factors besides the final sale price.

“The problem is that many advisers are pushing cash and that becomes a proxy for value,” said Ed Renenger, an attorney and ESOP specialist with Reading-based law firm Stevens & Lee. “In our experience if a business owner receives enough cash consideration to take care of their personal, family and charitable needs, it frees them up to think about other value drivers. There are lots of owners that find value in other things, such as legacy, community and employees.”

A sale to employees often entails risk and complications that don’t arise during a sale to a third party, Renenger and other advisers acknowledged. But the complexity ultimately is no greater than it is for a more typical sale.

“The reality is that the transition of a business to a third party, with the exception of an intergenerational transfer, is a very emotional event for the owner,” Renenger said. “It’s a complicated transaction that involves a detailed examination of current operations, current compliance with the law, current financial statements in ways that may feel very intrusive, and a sale to an ESOP is not unique in that.”

The ESOP, however, creates an opportunity to reward employees and preserve a business owner’s legacy, advocates said. And there are tax benefits, Renenger said. For one, an ESOP is considered a retirement plan, so a company that buys stock for its employees via contributions to an ESOP can use pre-tax dollars to do so, just like it would if it were making contributions to an employee’s 401(k) account.

Employee ownership also dovetails with changing expectations for the workplace, said Roger North, president of North Group Consultants Inc., a Lititz-based leadership consulting firm.

After World War II, workplaces followed a command-and-control approach fashioned along military lines, North said. Employees mostly accepted decisions handed down from above.

People entering the workplace today expect to have greater input into decision-making, he said. An ownership stake, whether held by children or employees, can help sharpen that input.

“My observation would be, if you don’t shift to that way of thinking, particularly over the next 10 to 15 years, you’ll likely be behind your competition,” North said.

It’s a way of thinking that has become ingrained at business software company Cargas Systems Inc. Employees have owned a growing stake in the company since 1998, said founder and CEO Chip Cargas.

Cargas now owns about 40 percent of the company. About 70 of the firm’s 100 employees hold the remaining 60 percent. Employees have two opportunities a year to buy at least $600 worth of stock. Shareholders help elect the company’s board, but all employees have access to the company’s financial performance and profit-sharing bonuses and other perks.

Cargas may no longer be the majority owner. But, he said, he feels he has a more engaged workforce and a sustainable company where people want to work. They pitch in when times are hard and celebrate when times are good.

“When we started employee ownership, I was 100 percent owner of a small pie,” he said. “Today I’m the 40 percent owner of a much larger pie and 40 percent of that much larger pie dwarfs the 100 percent of the smaller pie.”

The pie, he said, would not have grown as large without the effort and engagement of employee-owners. “Yes, we have a hierarchical organizational structure with titles and whatnot, but the way we operate is so collaborative,” he said.

And Cargas doesn’t have to fret about what will happen to the company when he retires. The succession is already under way, allowing employees to focus on customers.

“We don’t need to be worried about shocks to the system from huge ownership changes,” Cargas said.

As they move ahead, Assets and Project Equity plan to do more than raise awareness. Their goal eventually is to conduct feasibility studies for companies interested in employee ownership and to work with them to make it happen. Details are still being worked out, Dalen said.

Project Equity already has undertaken several transitions in the San Francisco area and has been developing studies for companies in western North Carolina, where it is working with a local partner called Industrial Commons, Lingane and Abell said.

The chief risks for retiring business owners include ensuring employees are prepared to become owners, both mentally and financially.

“Most small businesses are looking to rely on key employees who have management potential, who can keep the ship sailing and keep things going,” said Peter Kraybill, an attorney and leader of the corporate practice group at Lancaster County law firm Gibbel Kraybill & Hess LLP.

The key employees also need money to pay for the business. It typically involves a combination of debt and a promise to pay the selling owner over time as the buying employees acquire ever-greater chunks of the company, Kraybill said.

Among the risks is less-than-complete payment to the seller, especially if the new owners stumble during the transition, Kraybill said. The new owners may not buy in at the original rate preferred by the seller, or they may not earn the full confidence of customers.

“It’s quite a bit to navigate for an owner,” Kraybill said. “There are a lot of nervous-making moments.”

But, he said, there is a risk when a business is sold to an outside party. A third party could require payments over time instead of in a lump sum, and it may run the company very differently.

“That’s also a risk to a departing owner who very often, particularly for small businesses, has built this as their life work,” Kraybill said.